When Life Gives you Smoke Tainted Grapes, Make... Liquor?

Story by Margot Mazur / Originally Published in June 2022 (Wine Zine 06)

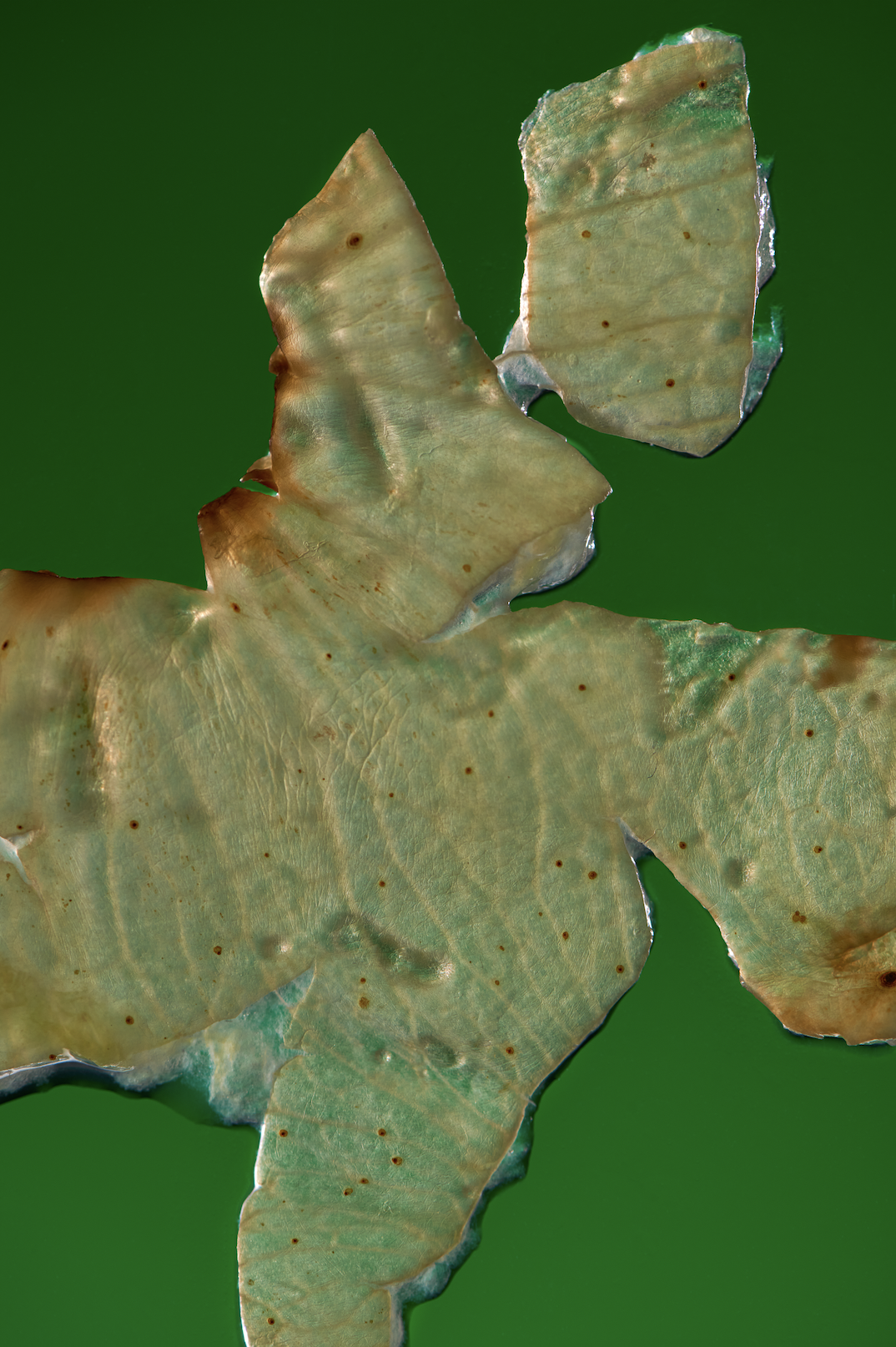

Image by Elmer Driessen

In today’s landscape, you can’t talk about winemaking without talking about climate change. Climate change has always been a concern for wine production, but recent rising temperatures, droughts, and changing sea levels have heavily impacted the soil and temperatures that affect grape production and wine flavor. In the last few years, California and Oregon winemakers have added a destructive climate change-related ailment to their list of concerns–wildfires. The 2020 wildfire season was the worst season for fires on record in California, burning through 4.1 million acres, and cutting the 2020 vintage down from 2019 by 13.8%, or 3.5 million tons of grapes. Wineries and vineyards suffered from the fires, people lost their jobs, and many winemakers found that the grapes they were able to harvest suffered from smoke taint.

“Winemakers across the West Coast were suddenly faced with a grim choice. If their grapes came back as smoke tainted, or their wines were tasting faulty, what should they do with that product?”

Smoke taint happens when smoke gets into the grapes that are hanging on the vine. A molecule called guaiacol binds to the sugar in the grape juice, releasing smoky flavor when that sugar breaks down into alcohol during the fermentation process. Smoky wine may sound delicious, but the flavors feel more like ash or overly smoked meat, completely taking over the wine’s profile and making a wine essentially undrinkable. “I couldn’t do anything [with the wine]. I took the grapes. I made wine with them and the wine just kept getting worse and worse. I have a Ramato that tastes like beef jerky,” says winemaker Colin Shirek of Oregon’s Alto Cirrus.

To find out whether grapes are smoked out, winemakers spend a lot of money on lab fees. Bree Stock of Oregon’s Limited Addition Wines worked closely with a lab. “We analyzed everything before we harvested, which is how we knew what to pick and what not to pick. We spent a lot of time and a lot of money sending everything to laboratories and doing extensive testing.” Winemakers across the West Coast were suddenly faced with a grim choice. If their grapes came back as smoke tainted, or their wines were tasting faulty, what should they do with that product?

In the interest of sustainability and getting some income out of their smoky harvests, some winemakers turned to distillation in order to give their wines longevity. Brianne Day, winemaker at Day Wines in Oregon, sensed an opportunity to use her grapes to make amaro. “We wound up with about 1500 gallons of wine that was so smokey we couldn't bottle it as wine. So we sent this out for distillation with Freeland Spirits and when the brandy came back in, [my Assistant Winemaker] Colin worked studiously on it to create a specific version of amaro like I had described and we had come to agree was what we were shooting for–an Oregon Alpine amaro”.

Winemakers like Brianne Day who work with small local growers often have those growers rely on them for their paycheck. Growers may not have smoke insurance, which could run a farmer over $6,400 per ton of grapes–a price so high that many growers would rather take the risk. “It’s a shockingly small percent of growers [I worked with] who did have smoke insurance, under 10%,” Brianne says. “I have a responsibility to uphold my grower contracts–they can’t sit it out, they don’t have that option. If you can make something out of [the grapes], I feel that you should.”

The Crimson Wine Group also turned to distilling, choosing to use their smoke tainted juice as a fundraising opportunity for California Fire Fund. Winemaker Nicolas Quillé worked with Hangar 1 Vodka to turn their juice into Smoke Point Vodka–100% of sales of the vodka were donated.

Eric Lee, Hangar 1 distiller, was on board to test whether making a clear spirit from smoky juice was a viable option. “We did some experiments, and it turns out that the smoke character does not come across, especially in a vodka distillation. Since we distilled to such a high proof in a relatively high purity of spirit–at the end result, no smoke character is coming through. What we did get was a wonderful wine-based vodka.” For Eric, making a vodka out of these grapes was a way to spread awareness about fire season and move the juice at the same time. “We really want to bring attention to the seriousness and the intensity of the fire season and how it's really affecting all of us. It's not just a handful of regions. It's really the whole state.”

“We really want to bring attention to the seriousness and the intensity of the fire season and how it’s really affecting all of us. It’s not just a handful of regions. It’s really the whole state.”

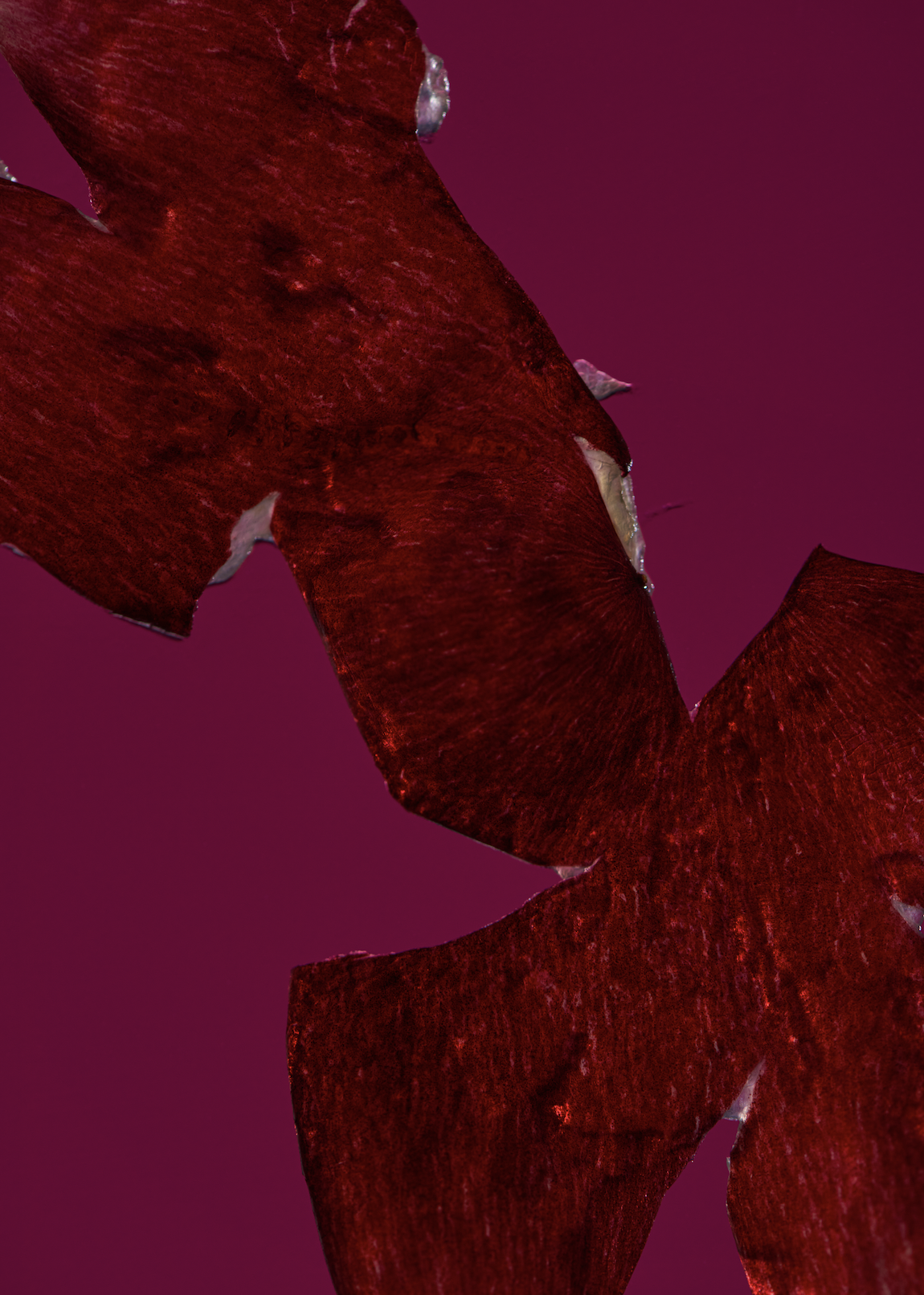

Image by Elmer Driessen

It’s clear to West Coast winemakers that wildfires are not going away anytime soon and that they’ll have to deal with the burning effects of climate change into the future. It’s time to start thinking about sustainability, and how they’ll use smoke-affected grapes in the future, with distillation as a front line solution. Nicolas Quillé is sure that winemakers will have to start pivoting in their production. “I am certain that wildfires are going to be a problem going forward and that certainty is pushing us to think broadly about how we are going to operate.” In the coming vintages, we may see more wine-based amaros, vodkas, and brandys, and I’m here for that.